Silicon–carbon (Si–C) anodes materials are regarded as one of the core enabling technologies for next-generation high-energy-density lithium-ion batteries. They are designed to overcome the intrinsic limitation of conventional graphite anodes, whose theoretical specific capacity is only 372 mAh/g, and to enable a major leap in battery energy density.

I. Why Choose Silicon? Why Must It Be Composite?

The Outstanding Advantages of Silicon

- Ultra-high theoretical capacity

Pure silicon has a theoretical specific capacity of approximately 4200 mAh/g, more than ten times that of graphite. - Appropriate lithium insertion potential

Slightly higher than graphite, offering improved safety and reduced risk of lithium plating. - Abundant resources and environmental friendliness

Silicon is widely available and environmentally benign.

The Critical Drawbacks of Silicon (“Achilles’ Heel”)

- Severe particle pulverization

Mechanical fracture during cycling leads to loss of electrical contact and detachment from the current collector. - Unstable solid electrolyte interphase (SEI)

Continuous rupture and regeneration of the SEI layer consume electrolyte and lithium, resulting in low Coulombic efficiency and rapid capacity fade. - Extreme volume expansion

Silicon can undergo more than 300% volume expansion during lithiation, which causes:- Structural collapse

- Electrode cracking

- Loss of electronic conductivity

- Poor intrinsic electrical conductivity

Significantly inferior to graphite.

The Role of “Carbon”

- Mechanical buffering matrix

Flexible carbon materials (amorphous carbon, graphite, graphene, etc.) accommodate silicon’s volume changes and prevent structural failure. - Conductive network formation

Carbon significantly improves the overall electrical conductivity of the composite. - SEI stabilization

A more stable SEI forms on carbon surfaces, limiting excessive direct contact between silicon and electrolyte.

Therefore, silicon–carbon composite design is an inevitable technological pathway to balance ultra-high capacity with long cycle life.

Mainstream Silicon–Carbon Composite Process Routes

The core concept is to engineer silicon–carbon architectures at the nanoscale to mitigate mechanical stress during cycling.

Core–Shell (Coating) Structures

Concept:

Silicon particles are encapsulated by a uniform carbon shell.

Process:

Nano-silicon or silicon oxide particles are coated with carbon via chemical vapor deposition (CVD), polymer pyrolysis, or liquid-phase coating.

Features:

- Carbon shell provides continuous electronic conduction pathways

- Suppresses outward volume expansion of silicon

- Isolates silicon from direct electrolyte attack

- Enhances cycling stability and Coulombic efficiency

- Precise control of carbon thickness is critical

Embedded / Dispersed Structures

Concept:

Silicon nanoparticles are uniformly dispersed within a continuous carbon matrix, similar to “raisins embedded in bread.”

Process:

Nano-silicon (<100 nm) is mixed with carbon precursors (resins, pitch, etc.), followed by carbonization to form a composite matrix.

Features:

- Carbon matrix acts as a continuous stress-absorbing phase

- Prevents silicon agglomeration

- Improves electrode mechanical integrity

- Moderate capacity with improved long-term cycling performance

- Relatively scalable and cost-effective

Porous / Framework Structures

Concept:

A rigid porous carbon framework provides internal void space to accommodate silicon expansion.

Process:

Porous carbon materials (carbon nanotubes, graphene aerogels, activated carbon) are prepared first, followed by silicon deposition or infiltration (e.g., CVD).

Features:

- Large internal void volume effectively buffers expansion

- Robust structural stability

- Excellent lithium-ion and electron transport pathways

- High rate capability

- Complex fabrication and higher cost

Bonded-Type Structure (Silicon Oxide–Carbon, SiOₓ–C)

(Currently the Most Industrialized Route)

Concept:

Silicon monoxide (SiOₓ) forms a self-buffering composite during lithiation.

Material Characteristics:

Upon lithiation, SiOₓ forms:

- Active silicon nanodomains

- Inactive lithium silicates / lithium oxide phases acting as internal buffers

Process:

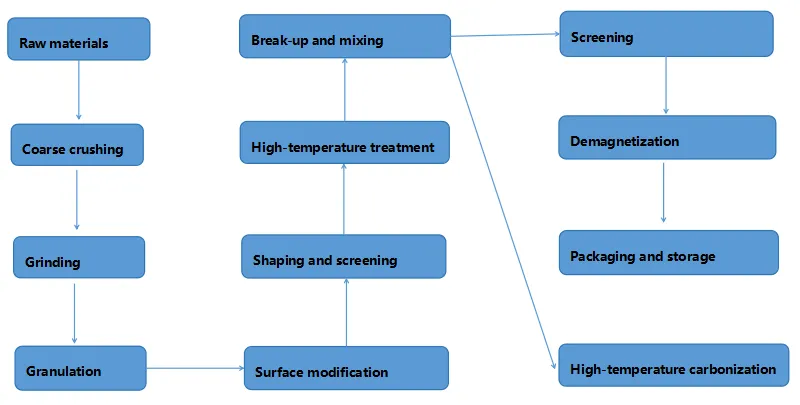

SiOₓ particles are mixed with carbon sources (pitch, resin), granulated, and carbonized to form secondary particles with carbon bonding and coating.

Features:

- Superior cycling stability compared to pure silicon

- Lower first-cycle Coulombic efficiency (requires pre-lithiation)

- Excellent structural integrity

- Widely adopted in high-end power batteries (e.g., Tesla 4680 cells)

- Currently the most mature commercial silicon-based anode technology

Key Preparation Technologies

Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD)

Applications:

- Carbon coating on silicon particles

- Silicon deposition within porous carbon frameworks

Key Controls:

- Temperature

- Carbon source gas flow (methane, ethylene, etc.)

- Deposition time

- Carbon layer thickness and graphitization degree

High-Energy Mechanical Ball Milling

Applications:

- Physical blending of micron-scale silicon with graphite or carbon black

- Preliminary particle refinement and composite formation

Key Controls:

- Milling time and intensity

- Atmosphere control

- Prevention of contamination and over-amorphization

Spray Drying and Pyrolysis

Applications:

- Formation of uniform silicon–carbon secondary microspheres

Process:

Silicon nanoparticles and carbon precursors (e.g., sucrose, polymers) are spray-dried and then carbonized.

Key Controls:

- Precursor selection

- Droplet size

- Thermal decomposition conditions

Pre-Lithiation Technology (Critical Supporting Process)

Purpose:

To compensate for irreversible lithium loss during initial SEI formation and improve first-cycle Coulombic efficiency.

Methods:

- Direct anode pre-lithiation (lithium foil contact, stabilized lithium metal powder – SLMP)

- Cathode lithium compensation (lithium-rich additives)

Importance:

Pre-lithiation is a decisive factor for the commercial viability of silicon–carbon anodes.

Technical Challenges and Development Trends

Current Challenges

- High cost

Nano-silicon, SiOₓ synthesis, and complex composite processes increase production cost. - Trade-off between first-cycle efficiency and cycle life

- Volumetric energy density limitations

Low tap density and expansion accommodation reduce practical volumetric gains. - Electrolyte compatibility

Specialized electrolyte additives are required to form robust SEI layers.

Future Development Trends

- Advanced material design

Transition from microstructural optimization to atomic and molecular-level control. - Process innovation and cost reduction

Development of scalable, low-cost nano-silicon and composite technologies. - Full-cell system integration

Co-development with high-nickel cathodes, advanced electrolytes, and solid-state batteries. - Increasing silicon content

Gradual increase from 5–10% toward >20% silicon, while maintaining cycle stability.

Conclusion

The core of silicon–carbon anode technology lies in “nanostructuring + compositing + structural engineering.”

By intelligently combining silicon’s ultra-high capacity with carbon’s buffering and conductive functions, it becomes possible to harness silicon’s advantages while suppressing its intrinsic drawbacks.

At present, SiOₓ–C composites have achieved large-scale commercialization, while nano-silicon–carbon composites represent the future direction for even higher energy density lithium-ion batteries. As processing technologies mature and costs continue to decline, silicon–carbon anodes are poised to become a standard configuration in next-generation high-performance batteries.

“Thanks for reading. I hope my article helps. Please leave a comment down below. You may also contact Zelda online customer representative for any further inquiries.”

— Posted by Emily Chen